became Tawedzera Dzangere for

three weeks in August and September. In Shona, the word

"tawedzera" means "we have increased," which is exactly what

happened to the Dzangare family while I was staying with them.

became Tawedzera Dzangere for

three weeks in August and September. In Shona, the word

"tawedzera" means "we have increased," which is exactly what

happened to the Dzangare family while I was staying with them.

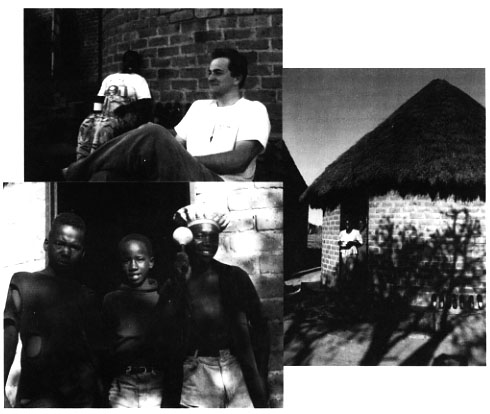

The Dzangares live in Gweshe Village, part of the Chiweshe

Communal Lands in Mashonaland Central Province. Baba (Father)

Dzangare supports his family by fishing in a local man-made lake and

by cultivating small plots of cotton, maize and squash. Amai (Mother)

Dzangare spends her days cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the

children.

I was the Dzangare's third and youngest son. The eldest of my

host brothers was living in Harare, but the Dzangare's other son,

Warren, was still living at home, along with Amai Dzangare's younger

brother Evans and their cousin Innocent.

Culture shock both frustrates and entertains. Living in rural

Africa, I had to get used to entirely alien concepts of privacy,

gender relationships, and daily subsistence.

The most immediate and disorienting of these was the first -- the

complete lack of personal space. My host brothers would follow me to

the outhouse -- chimbuzi in Shona -- because they wanted to make sure I would be

safe. While I was away at school, a forty-five minute walk from the

Dzangare homestead, my host sisters would clean and organize my few

personal items. At night, I would cram into a small double bed with

two or three of my big host brothers.

After two weeks in Gweshe, I thought I had acclimated completely,

until, that is, my host brothers found the one letter that I had

received during my three weeks in the village. I ducked out to the

chimbuzi

for no more than two minutes, and when I returned to our hut, Evans

and Innocent were reading a personal letter that I had received from

my girlfriend.

At first, I was intensely angry, but I quickly gained my

composure and realized that my host brothers' intentions were not

malicious; they were just curious about what my girlfriend had to

say. At the end of her letter, my girlfriend wrote, "Don't forget to

teach me some Shona: 'Hello,' 'Goodbye,' 'Thank you,' 'Do you want to

do it doggy-style?' -- you know, just the basic vocabulary will

do."

My host brothers understood everything in the letter. Well,

almost everything: "Tawedzera, what's

'doggy-style?'" they asked.

"Well, brothers," I explained, "in my culture, if you read

someone else's mail, you must write to the person who wrote the

letter if you have any questions about it." Thus began a

correspondence between my girlfriend in Washington, D.C. and my host

brothers in a rural Zimbabwean village.

On another

night, while I was complaining to my notebook about my lack of space,

I heard a loud ruckus brewing outside. I jumped up, grabbed my

flashlight and went to investigate.

On another

night, while I was complaining to my notebook about my lack of space,

I heard a loud ruckus brewing outside. I jumped up, grabbed my

flashlight and went to investigate.

Boys with sticks were prowling around the homestead, shouting for

flashlights and calling their dogs. I found Warren among the band of

boys.

"What the hell is going on?" I asked.

"They have trapped a pig in that field," he said, pointing to the

corral behind our hut.

"Well, let's go catch it," I said, running into the field with my

flashlight.

Warren started yelling at me, "Tawedzera, come back, come

back!"

"Why?" I shouted.

"Tawedzera, that's a wild pig, a njiri, not a domesticated

pig. It is a deadly animal," he explained.

Warren explained that some dogs had picked up the scent of the

njiri and

chased it towards the village. When some boys saw the animal, they

grabbed wooden clubs and other blunt weapons and went in pursuit.

"What are they going to do to it when they catch it?" I asked

Warren.

"They're going to kill it!" he replied.

Using the dogs and the blunt weapons, they planned to corner the

animal and beat it to death. Warren added that the animal would

probably be killed only after one or two of the boys had been injured

-- either by the animal's huge tusks or by another boy's poorly

wielded blunt weapon.

"And what will they do with it after they kill it?" I asked.

"They will divide up the meat and bring it back to their

mothers," Warren replied.

By this time, a huge growd had gathered at the homestead. The

boys were getting frantic and it appeared that the dogs had lost the

scent.

"What a shame," Warren said, "I think that the njiri has escaped."

"Good for the njiri," I said.

"No," said Warren, "we are sad when a njiri escapes because

njiri meat

is very tasty."

Warren looked after me for those entire three weeks. He even went

so far as to provide me with a woman on one of my last nights in the

village. In Shona culture, men must buy their wives for a hefty price

-- about ten cows or the cash equivalent. For this reason, to be

given a woman for free is a great honor indeed. Unfortunately, I

didn't realize what was happening until after I had missed my chance

to accept Warren's gift. A strange woman arrived at the homestead one

night and after she disappeared, Warren asked me why I had not

accepted her.

"What are you talking about?" I asked.

"I brought her here for you," he said.

A long conversation about gender politics in my culture ensued.

After about an hour, Warren understood that it would have been

inappropriate for me to accept his generous offer.

While I refused the proffered wife, I did manage to pick up

another equally memorable souvenir. To call this memento "foot

fungus" would be a serious understatement. One of the programme staff

called it "jungle rot," which seems more accurate. I cannot be

exactly sure where I contracted the jungle rot, but chances are that

it came from the chimbuzi. Naive American

that I am, I usually visited the chimbuzi with bare feet.

By my third week in the village, the jungle rot had ravaged the first

several layers of skin on the heel of my right foot. My foot looked

like ground zero after a missile strike.

The only thing worse than the severe tissue damage, however, was

the smell. I won't try to describe it. I tried to keep my foot clean

and dry, but my condition just got worse.

Through the programme, I eventually tracked down a doctor who

prescribed Nidrox, a powerful antifungal medication. The Nidrox

stopped the spread of the fungus but did not eliminate it. Two weeks

after I started taking the Nidrox, my prescription ran out and, since

I was not in Harare, I could not get it refilled. The fungus came

back with a vengeance. Eventually, however, it went away on its own.

Too bad -- now I have less to show from my trip.

[ BACK ]

![]() became Tawedzera Dzangere for

three weeks in August and September. In Shona, the word

"tawedzera" means "we have increased," which is exactly what

happened to the Dzangare family while I was staying with them.

became Tawedzera Dzangere for

three weeks in August and September. In Shona, the word

"tawedzera" means "we have increased," which is exactly what

happened to the Dzangare family while I was staying with them.

![]()